Intraocular Melanoma

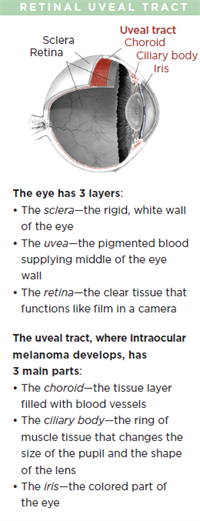

Malignant intraocular melanoma is the most common eye cancer in adults. The tumor affects the uveal tract, which is the middle layer of the wall of the eye.

The most common site for ocular melanoma is the choroid, followed by the ciliary body, and the iris.

In the United States, choroidal melanoma affects approximately 2500 people per year with an incidence of 6 per million. Ocular melanoma is more common in fair-skinned individuals. Smoking increases the risk for the condition, which typically affects people in their 60s. Unlike skin (cutaneous) melanoma, ocular melanoma is generally not associated with previous sun exposure.

In rare cases, a genetic condition may increase a person’s chances of developing ocular melanoma, but it does not “run” in families. Children, brothers, sisters, and parents of ocular melanoma patients may be screened, but are almost universally free from the condition.

Unlike other severe eye diseases, ocular melanoma does not show signs or symptoms in the vast majority of patients. When symptoms are present, they are non-specific and include floaters, flashes, or loss of vision from the affected eye. Rarely is the eye red or painful. As such, uveal melanoma is most often recognized by the primary eye care specialist. In these instances, the patient is typically referred to a retina specialist and often an ocular oncologist (eye cancer specialist).

Diagnostic testing

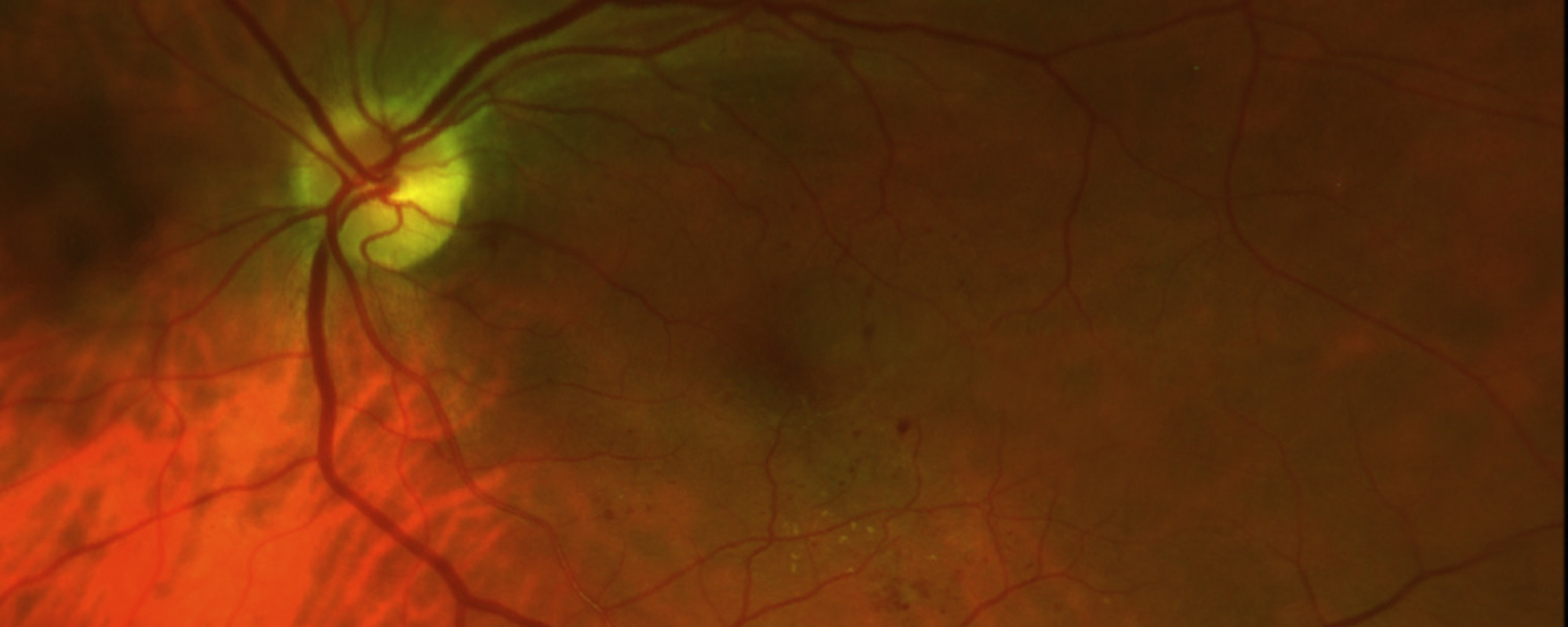

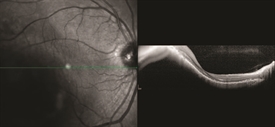

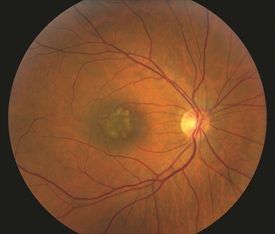

Figure 1. OCT analysis of macular choroidal melanoma medium. Photo credit: Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA

During a targeted tumor examination, diagnostic testing typically includes a complete eye exam with dilation of the fundus, indirect ophthalmoscopy, tumor photography (fundus photography), tumor ultrasound, and vascular studies of the tumor (fluorescein angiography, indocyanine green angiography, spectral-domain OCT angiography (sd OCT)), along with laser studies of the macula. These imaging studies evaluate the tumor, allowing documentation of the clinical diagnosis. (See Clinical Terms section for other related screenings.) The ocular tumor is then staged—a process that defines the extent of tumor based on its length, width, and height.

Historically, tumors were sized using the Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) staging criteria, but recent advances in staging now incorporate multiple factors preoperatively and are often modified by inclusion of tumor genetics obtained during surgery. The Eighth Edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual has updated the staging of ocular melanoma. A biopsy of the melanoma reveals tumor genetics that can give the patient and physician an understanding of the risk of the tumor spreading.

Diagnosis

An ocular oncologist will typically make and discuss a diagnosis at the time of the completed examination. Unlike in other oncology specialties, a biopsy for diagnosis is rarely required. However, advances in genetic testing can only be utilized with the availability of a tumor tissue sample. These samples are taken after the clinical diagnosis of intraocular melanoma is made and are often gathered at the time of treatment. After diagnosis, treatment options that range from observation, laser, vitrectomy, radiation, or enucleation (removal) of the tumor-bearing eye are discussed.

For patients with high-risk tumors, or those requiring surgery, further testing is indicated to determine whether the eye tumor is present outside of the eye (metastatic screening) or to ensure the patient can be safely taken to the operating room for treatment.

In many cases, the patient is seen by a primary care eye specialist, followed by a vitreoretinal specialist, and finally by the ocular oncologist. Most patients do not need an additional evaluation after their diagnosis to be appropriately treated.

Tumor Sizing

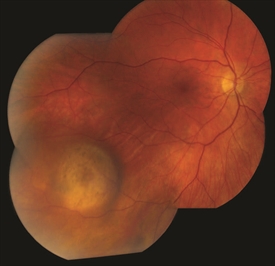

Figure 2. Small benign macular choroidal freckle/nevus. Photo credit: Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA

Tumor sizing Typically, ocular oncologists use 5 categories for tumor sizing: small, medium, large, extra-large, and a fifth category for borderline small tumors called atypical nevi (singular: nevus). Tumor sizing is important, as it has an impact on treatment options for the patient. Choroidal nevi (sometimes called eye freckles) occur in approximately 20% of the population and are benign. They are thepotential precursor to choroidal melanoma, but there are certain clinical characteristics such as thickening that may give the nevus a higher risk for transformation into a melanoma. These atypical nevi should be photographed/ documented with baseline ultrasound and followed every 6 months.

Treatment and prognosis

• Observation: This treatment includes ongoing clinical evaluation of the tumor, typically to determine change. Often, patients are seen at 3 months, every 4 months, and ultimately every 6 months. Comprehensive testing is performed on each visit to assess any change in tumor size or characteristics.

Observation is typically limited to atypical nevi to monitor for change to a small melanoma. This treatment has been shown to be extremely effective when the follow-up visits are carefully maintained.

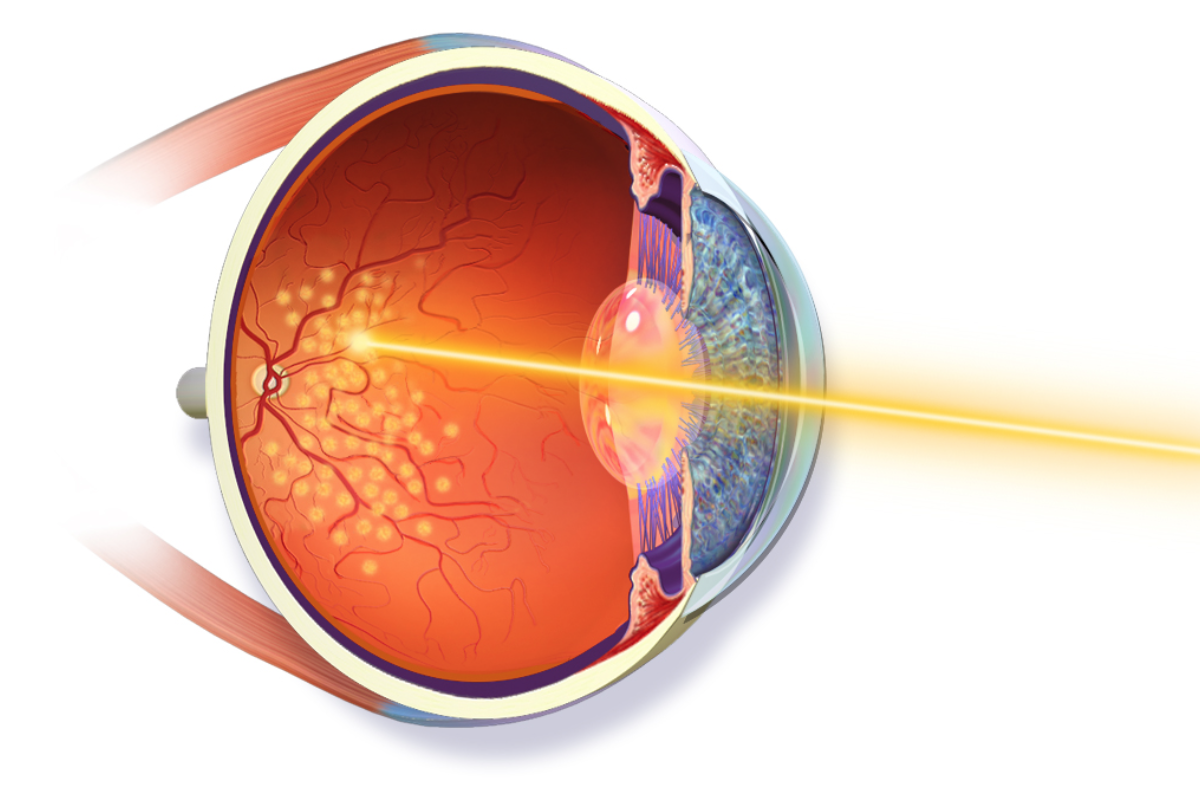

• Laser tumor ablation (LASER): Laser destruction (ablation) of a tumor has been effective but limited in its application due to penetration and secondary retinal damage. Recent advances have shown excellent success (efficacy) when tumor treatment is performed during vitrectomy surgery. Laser surgical approaches are typically offered as primary treatments for small ocular melanomas. Laser surgical approaches may be used as a primary treatment in some small ocular melanomas.

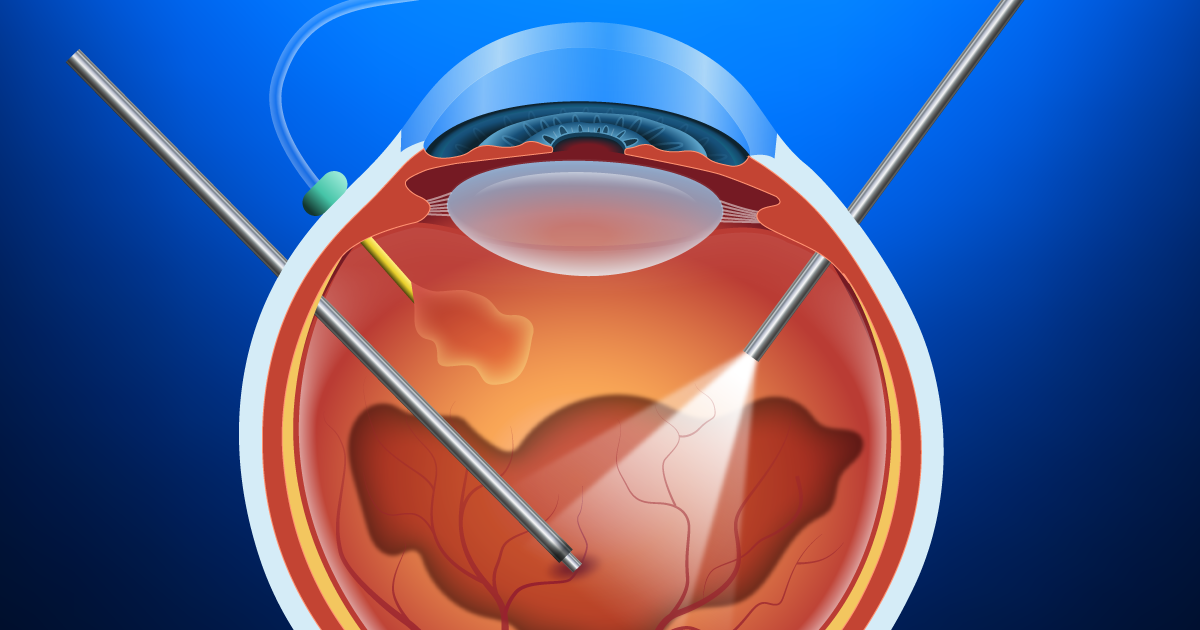

• Vitrectomy (micro-incision vitrectomy surgery, or MIVS): This is surgery to remove the vitreous gel (jelly-like substance inside the back compartment of the eye), remove tissue traction and scarring (membrane peeling), laser destruction of the tumor, biopsy of the tumor (fine-needle biopsy or FNAB), and suppression of post-surgical inflammation. Additionally, MIVS surgery may be used to place silicone oil in the back compartment of the eye to stabilize the retina or potentially reduce radiation complications.

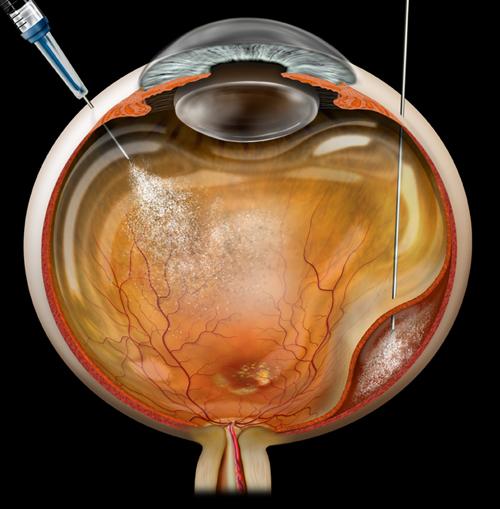

• Radiotherapy: Two major types of radiation treatment are routinely used for ocular melanoma— brachytherapy and charged-particle therapy.

- Brachytherapy is the most common radiation treatment for ocular melanoma; it uses a patch approximately the size of a quarter that is attached directly to the eye in surgery. The “patch” typically remains on the eye for 3 to 5 days and is removed in a second, brief operation. During the brachytherapy surgery, the eye is often biopsied for tumor genetic testing. The patch is shielded to protect the non-tumor tissues during the procedure. In many studies, this treatment has achieved tumor control in almost 100% of eyes.

- Charged-particle radiotherapy uses a beam of charged radiation particles to destroy the tumor. This treatment typically requires surgery to localize the tumor with small metallic clips sewn onto the eye to surround the tumor. These metallic clips help to localize the tumor so the charged particles can be directed precisely to the tumor. Charged-particle treatment is much less common for ocular melanoma, but has virtually identical success rates for tumor control.

• Enucleation: Removal of the entire eye to eliminate the tumor. This surgery is typically performed with reconstruction of the eye socket and placement of an implant. Enucleation is typically performed only for extra-large tumors, or for tumors that have failed initial treatment. No benefit has been shown for enucleation of smaller tumors compared with other treatments that preserve the eye.

Figure 3. Small/medium malignant choroidal melanoma. Photo credit: Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA |

Figure 4. Small/medium malignant choroidal melanoma after brachytherapy. Tumor size reduced by 40%. Notice small bleeding from the radiation. Photo credit: Timothy G. Murray, MD, MBA |

Genetic Testing

A major advance in ocular oncology has been the use of tumor genetics to define the genetic risk of tumors spreading outside of the eye (metastasis). Two genetic testing approaches are now available: gene expression profiling (GEP) and cytogenetics (chromosomal analysis). GEP testing yields 2 classes of tumor—class 1 (1a and 1b) and class 2.

These classes are statistically associated with risk for metastatic disease. We have learned from cytogenetics that alterations in chromosomes 3, 6, and 8 greatly impact the risk of developing metastatic disease. These genetic tests require tumor tissue (biopsy) and are important for prognostication (risk assessment for metastatic disease) but do not influence the primary treatment of the tumor. Recent studies have shown that genetic testing may be performed after primary treatment without compromising test results.

Ocular melanoma is the most common primary eye cancer of adults but, fortunately, remains a rare cancer. Expert treatment is recommended for each patient.