Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion

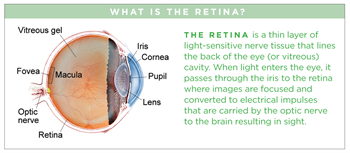

Retinal vein occlusions occur when there is a blockage of veins carrying blood with needed oxygen and nutrients to the nerve cells in the retina. A blockage in the retina’s main vein is referred to as a central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO), while a blockage in a smaller vein is called a branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO).

Symptoms

BRVO causes a sudden, painless loss of vision. If the affected area is not in the center of the eye, BRVO can go unnoticed with no symptoms.

In rare cases of an undetected vein occlusion, visual floaters from a vitreous hemorrhage (blood vessels leaking into the vitreous gel of the eye) can be the main symptom; this is caused by development of abnormal new blood vessels (neovascularization) in the retina.

Causes

Most BRVOs occur at an arteriovenous crossing—an intersection between a retinal artery and vein. These vessels share a common sheath (connective tissue), so when the artery loses flexibility, as with atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), the vein is compressed.

The narrowed vein experiences turbulent blood flow that promotes clotting, leading to a blockage or occlusion. This obstruction blocks blood drainage and may lead to fluid leakage in the center of vision (macular edema) and ischemia—poor perfusion (flow) in the blood vessels supplying the macula.

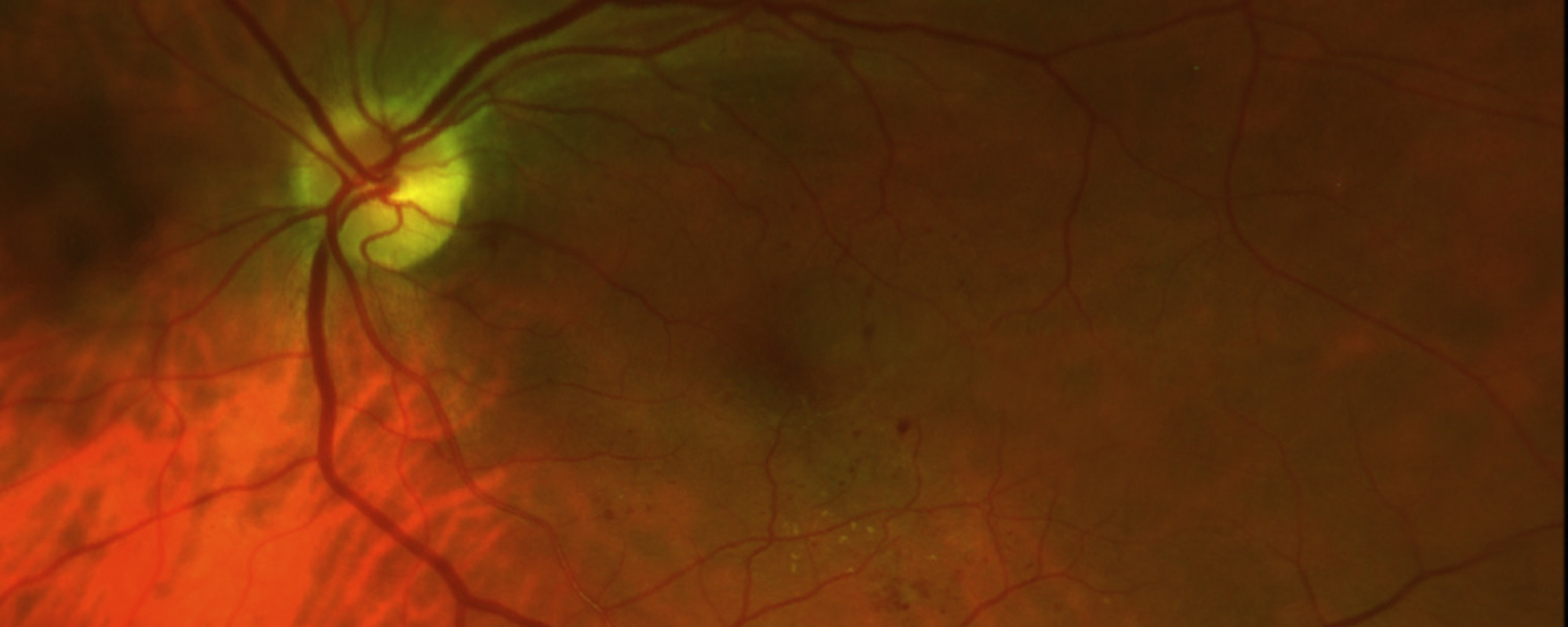

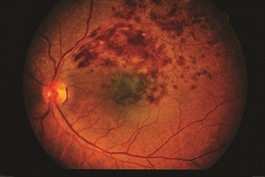

Figure 1. Branch retinal vein occlusion: Retinal hemorrhage in only a sector of the retina is seen. Cotton-wool spots (white lesions amid the hemorrhages) signify focal ischemia (inadequate blood supply). Foveal edema (swelling with fluid) is also present. Photo courtesy Anat Loewenstein, MD |

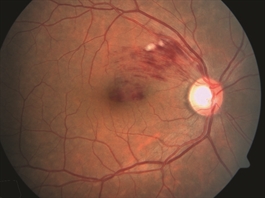

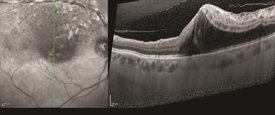

Figure 2. BRVO with macular edema. David Callanan, MD, Texas Retina Associates. BRVO/CHRPE. Retina Image Bank 2014; Image 15926. © American Society of Retina Specialists. |

Risk factors

The common risk factors for BRVO are:

- Uncontrolled high blood pressure

- Being overweight or obese (increased body mass index)

- Cardiovascular (heart) disease

- Glaucoma

- In younger patients who suffer BRVO, an abnormal tendency to develop blood clotting is also possible

Diagnostic testing

Most often, BRVO is diagnosed by an eye exam that shows retinal hemorrhage (blood vessels leaking into the retina), thickened and twisted blood vessels, and retinal edema (swelling with fluid).

Figure 3 OCT image of macular edema secondary to BRVO. There is a cystoid macular edema mainly in the superior part of the macula, effecting the superior temporal vein. Photo courtesy of Anat Loewenstein, MD

Two types of retinal imaging tests aid the diagnosis of BRVO:

FA provides images of fluid leaking from damaged or abnormal retinal vessels, demonstrating:

- Venous stasis (congestion and slowing of circulation)

- Edema (swelling with fluid)

- Ischemia (inadequate blood supply) or

- Retinal neovascularization (abnormal growth of new blood vessels in the retina)

OCT provides detailed images of the central retina, allowing detection of macular edema and fluid outside the macula (Figure 3).

FA is very valuable for detecting BRVO and the flow of the blood vessels. Once BRVO has been found, OCT is used to provide a better assessment of whether macular edema is present, and if so, how severe it is.

Treatment and prognosis

Treatment begins with identifying underlying risk factors and treating them. Risk factors are assessed using several methods:

- Blood pressure monitoring

- Determining if blood cholesterol or lipid levels are elevated

- Blood tests, if appropriate, to determine if there is an abnormal tendency to form blood clots

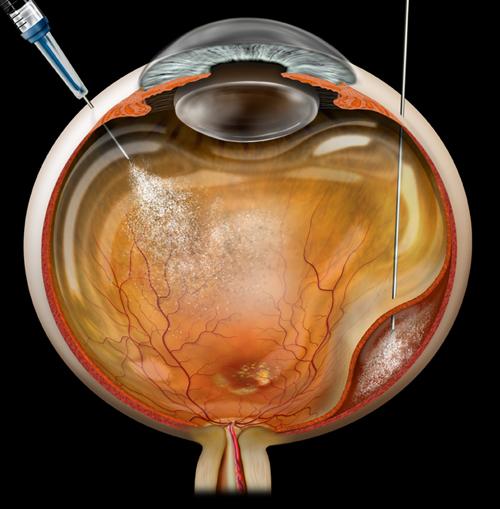

Eye treatment is aimed at treating retinal complications rather than at trying to relieve the blockage itself. Macular edema, the main reason for visual loss from BRVO, is often treated with intraocular (in-the-eye) injections of anti-VEGF drugs designed to stop the growth of abnormal new blood vessels in the eye and decrease leakage. Local anesthetic eye drops are given before the injections to numb the eye and minimize discomfort.

There are currently 3 anti-VEGF drugs:

- Avastin® (bevacizumab®)

- Lucentis® (ranibizumab®)

- Eylea® (aflibercept®)

In several large clinical studies, all 3 of these anti-VEGF drugs have demonstrated good results, with over 50% of patients enjoying significant visual improvement. The use of these drugs may require frequent retreatment, but injection schedules are determined on a case-by-case basis.

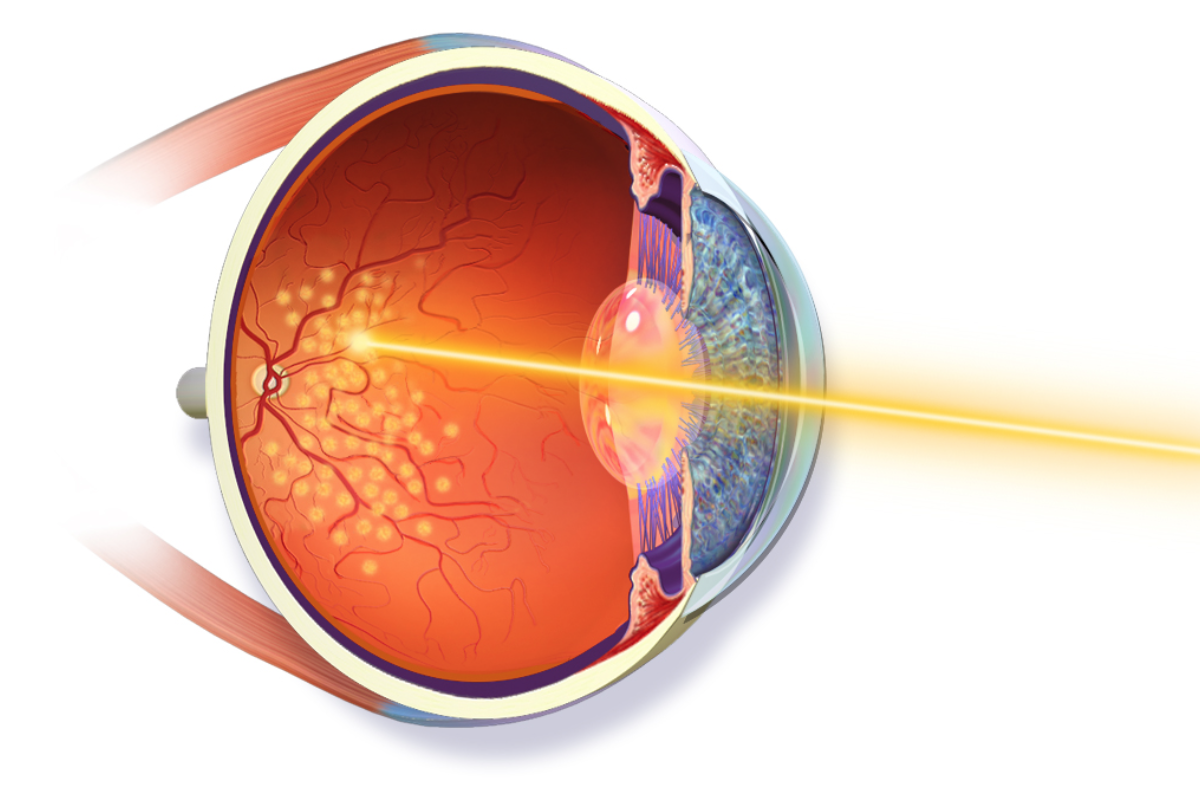

Laser treatment may be used along with anti-VEGF therapy in hard-to-treat cases. Laser therapy for macular edema involves applying light laser pulses to the macula in a grid pattern. In a large multi-center clinical trial, after 3 years of follow up, this treatment showed improvement of vision in approximately two-thirds of patients.

Intraocular injections of steroids are another potential treatment for eyes that don’t respond to anti-VEGF drugs. A clinical trial that evaluated steroid treatment using a slow-releasing steroid implanted in the eye (dexamethasone or Ozurdex®), showed that approximately 30% of BRVO patients enjoyed significant visual improvement following treatment.

While intraocular steroids can have some side effects such as an increase in eye pressure and cataract progression, in most cases, these side effects can be controlled.

Overall, BRVO carries a generally good prognosis. In fact, some BRVO patients don’t require treatment at all, either because the blockage did not involve the macula, or because they have not experienced a decrease in vision. Over 60% of patients, treated and untreated, maintain vision better than 20/40 after 1 year.

Complications

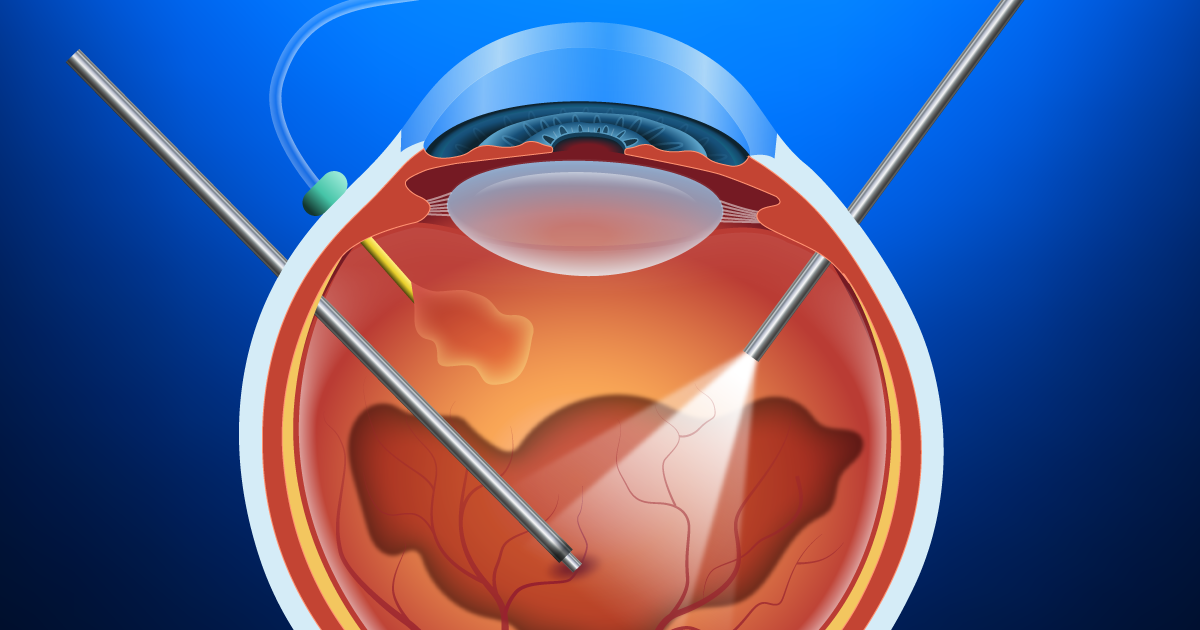

Retinal neovascularization is a potentially serious complication of BRVO in which an inadequate blood supply (ischemia) causes abnormal new blood vessels to grow on the surface of the retina. This growth can further decrease vision by causing vitreous hemorrhage that causes floaters and loss of vision, retinal detachment, and glaucoma.

When neovascularization develops, scatter laser photocoagulation therapy is used to create burns in the area of the vein occlusion (blockage). The aim is to try to lower the oxygen demand of the retina and thus stop the abnormal blood vessels from growing. Patients receive an anesthetic to numb the eye and make the treatment more comfortable.

Scatter photocoagulation has been shown to reduce neovascularization-related complications from 60% to 30%. Because only a few patients develop abnormal new blood vessels in the retina, not many need scatter photocoagulation treatment.