What is Toxoplasmosis?

A single-celled parasite called Toxoplasma gondii causes a disease known as toxoplasmosis. While the parasite is found throughout the world, more than 60 million people in the United States may be infected with the Toxoplasma parasite. Of those who are infected, very few have symptoms because a healthy person’s immune system usually keeps the parasite from causing illness. However, pregnant women and individuals who have compromised immune systems should be cautious; for them, a Toxoplasma infection could cause serious health problems.

A single-celled parasite called Toxoplasma gondii causes a disease known as toxoplasmosis. While the parasite is found throughout the world, more than 60 million people in the United States may be infected with the Toxoplasma parasite. Of those who are infected, very few have symptoms because a healthy person’s immune system usually keeps the parasite from causing illness. However, pregnant women and individuals who have compromised immune systems should be cautious; for them, a Toxoplasma infection could cause serious health problems.

How do people get Toxoplasmosis?

A Toxoplasma infection occurs by:

- Eating undercooked, contaminated meat (especially pork, lamb, and venison).

- Accidental ingestion of undercooked, contaminated meat after handling it and not washing hands thoroughly (Toxoplasma cannot be absorbed through intact skin).

- Eating food that was contaminated by knives, utensils, cutting boards and other foods that have had contact with raw, contaminated meat.

- Drinking water contaminated with Toxoplasma gondii.

- Accidentally swallowing the parasite through contact with cat feces that contain Toxoplasma. This might happen by

- cleaning a cat’s litter box when the cat has shedToxoplasma in its feces

- touching or ingesting anything that has come into contact with cat feces that contain Toxoplasma

- accidentally ingesting contaminated soil (e.g., not washing hands after gardening or eating unwashed fruits or vegetables from a garden)

- Mother-to-child (congenital) transmission.

- Receiving an infected organ transplant or infected blood via transfusion, though this is rare.

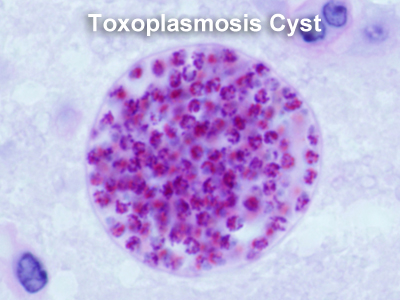

How Common is Toxoplasmosis?

The frequency of toxoplasmosis varies greatly worldwide. It is most common in Central America and central Africa, and much less common in the U.S. This variation can be explained partly by climate since temperature and humidity affect how long toxoplasma cysts remain infectious. Local culinary customs also play a role; areas where meat is served raw or undercooked have higher rates of infection. The use of fresh meat that has not been previously frozen is also associated with a greater risk of infection.

Once you have been infected with toxoplasma, you will have antibodies in your blood for the rest of your life. (Antibodies are produced by your immune system to combat specific infectious agents that have entered your body.) In the U.S., the rate of toxoplasma infection in women of childbearing age is 3 to 30%, depending on part of the country. On average, about 10% of reproductive-age women in the U.S. have had toxoplasmosis; in some countries, this percentage may be as high as 70 to 80%.

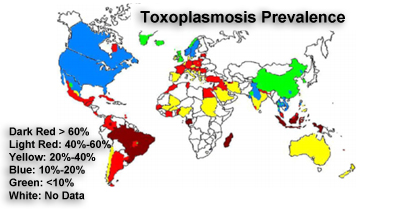

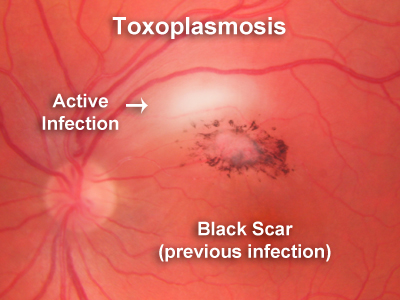

What are the Ocular Manifestations of Toxoplasmosis?

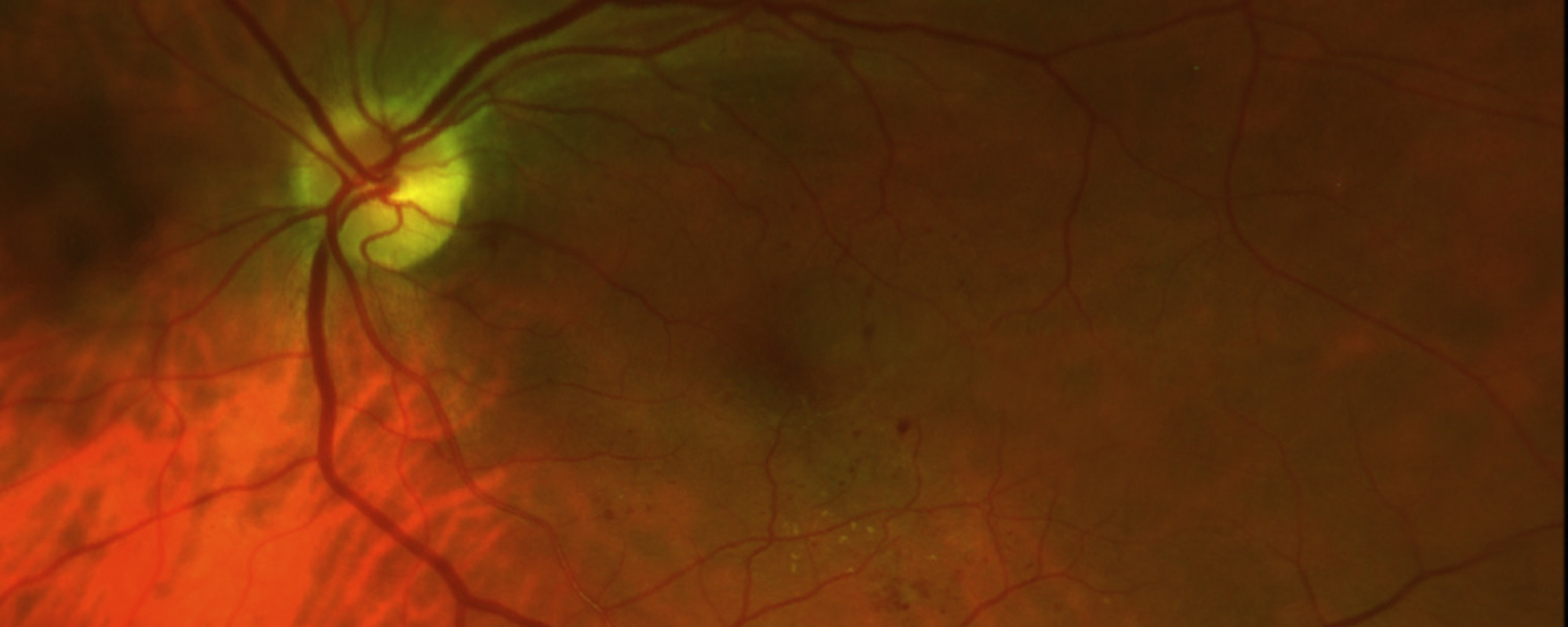

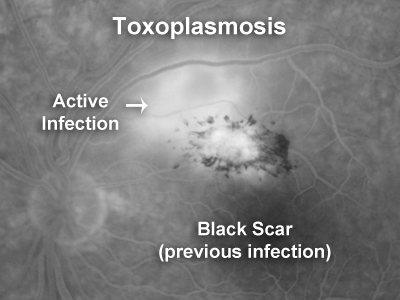

Toxoplasmosis is the most common cause of posterior uveitis, that is, inflammation in the back of the eye. When toxoplasmosis affects the retina and choroid, it causes a white spot in the retina, like the one in the accompanying photograph. It usually causes the eye to fill with white cells making the vision cloudy and full of small floaters. Most cases of toxoplasmosis choroiretinitis are recurrent. In those situations, the doctor will see a scar in the back of the eye from the previous episode with a white area of recurrent inflammation next to the scar. Toxoplasmosis can present in other ways. Sometimes it will present as isolated inflammation in the front of the eye, or inflammation in the retina only. It usually presents as inflammation of the choroid, retina and vitreous.

How is Toxoplasmosis Treated.?

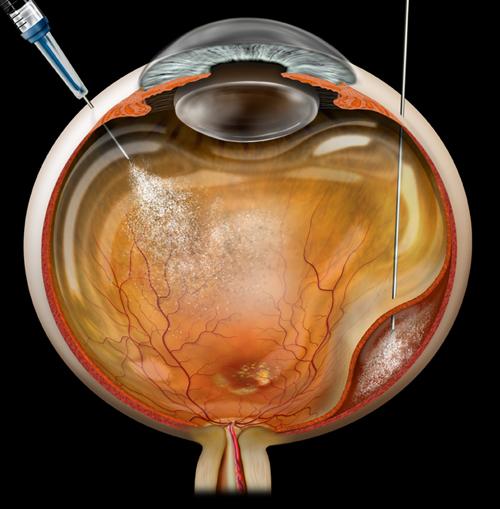

The need for therapy, type of drug treatment and duration of therapy needs to be individualised. It is determined by factors such as the location of the lesion, severity of the inflammatory response, threat to vision, status of the other eye and the immune status of the patient. The accompanying image shows a lesion very close to the fovea that needs treatment because it threatens the central vision. This image is a late fluorescein angiogram showing leakage of fluorescein dye in the area of active infection.

An episode of ocular infection is ultimately self-limiting in immunocompetent patients. If the infection involves the peripheral retina, has only mild associated inflammation and there is no involvement of the optic disc or macular region of the retina, then treatment is not necessary.

Therapy is usually needed for 6 to 12 weeks in immunocompetent patients and a response is determined clinically when the retinal lesions lose their fluffy white appearance, the vitreous clears and an atrophic chorioretinal scar with sharp margins develops.

Immunocompromised patients such as transplant recipients and patients with HIV infection may require long-term suppressive therapy. Pyrimethamine and/or sulfadiazine can be used to maintain control of infection.

Most treatments are active against the replicating form of the parasite (tachyzoite). Some newer antimicrobials kill encysted organisms (bradyzoites) in animal models, however there are no data available for human disease.

Combination drug therapy is preferred to achieve rapid resolution, minimise inflammatory damage and to minimise resistance. The most commonly used combinations are clindamycin and corticosteroids, and pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine and corticosteroids. Combination treatment results in smaller retinal scars and is frequently used to treat patients with macular involvement. Other combinations of antimicrobials can be used, but data are limited. Treatment with Bactrim Double Strength twice daily is effective in many cases.

Pyrimethamine is probably the most effective single drug. It interferes with replication as it inhibits the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase in the folate production pathway. Treatment consists of a loading dose of 25 mg three times on the first day followed by a daily dose of 25 mg. The main adverse reactions are bone marrow depression (particularly leucopenia and thrombocytopenia), nausea and other gastrointestinal adverse effects.

Human cells are able to utilise exogenous folate, while toxoplasma, which lacks transmembrane transport mechanisms for folate, depends on intra cellularly derived folic acid. Folinic acid 15 mg should be taken orally three times weekly to provide adequate dietary folic acid to prevent adverse effects, particularly bone marrow suppression, whenever pyrimethamine is used. A weekly full blood count is essential.

This is a sulfur analogue and acts as a competitive antagonist for para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA), one of the precursors of folate production. Treatment consists of a loading dose of 2 g followed by 1 g four times daily. Its main adverse reactions are malaise, gastrointestinal adverse effects and hypersensitivity. Other important adverse reactions include bone marrow suppression and crystallisation in the renal tubules.

Clindamycin interferes with protein synthesis. It is frequently used as a single drug or in combination with corticosteroids with excellent results. Recommended doses are 300 mg four times daily for 3-4 weeks followed by 150 mg four times daily for a further 3-4 weeks. Its serious adverse effects are diarrhoea and pseudomembranous colitis. Clindamycin has also been used as intraocular therapy by direct injection into the vitreous.